By Andrew Proulx MD

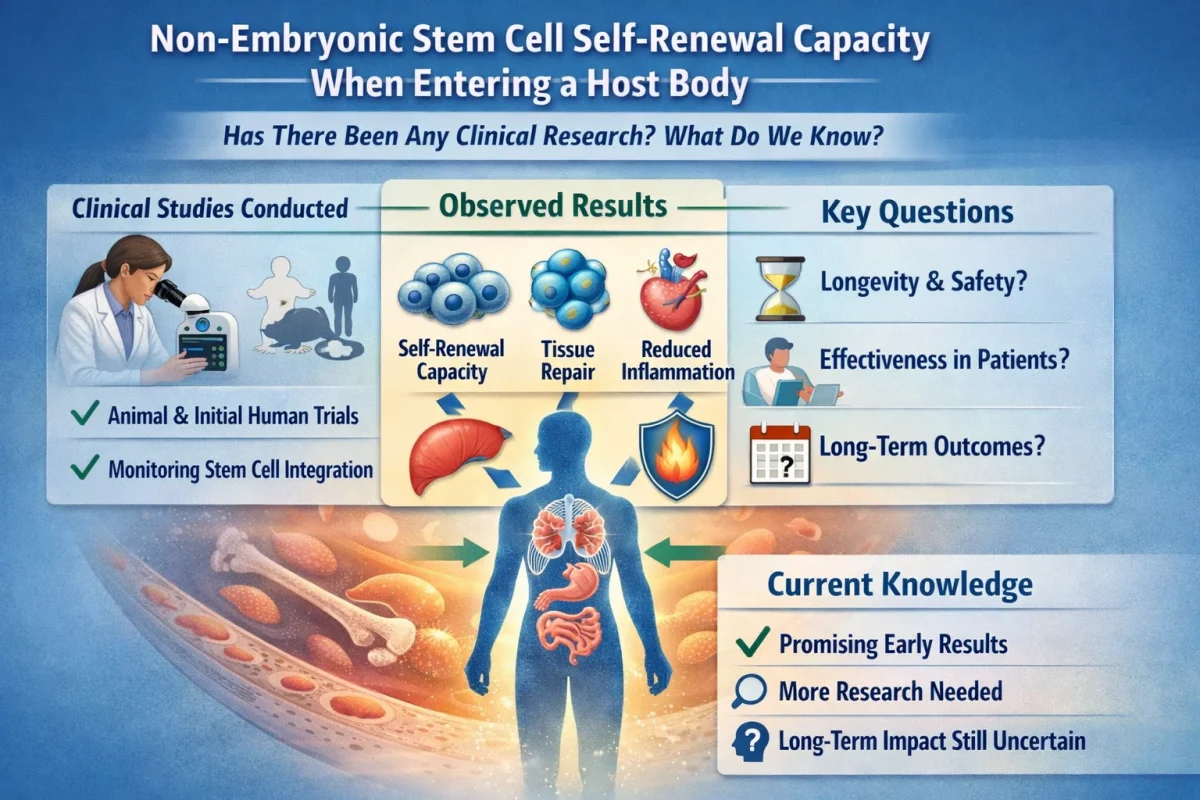

Non-embryonic (i.e., adult) stem cells can self-renew after entering a host body, meaning they can still divide to produce more stem cells while maintaining their undifferentiated state. The ability to self-renew is a cornerstone trait of stem cells that enables their robust abilities to promote tissue regeneration and repair. In this article, we will review recent research on non-embryonic stem cell self-renewal in a host body and highlight our present understanding.

Key Regulators

Current research is focused on identifying key molecular regulators of self-renewal. For example, a 2024 study out of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) discovered a self-renewal regulator that is responsible for the lost ability of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to self-renew in lab cultures.1 The investigators found that the Myc-interacting MYC target 1 gene and protein (MYCT1) play a role in helping stem cells sense their microenvironment, and these become downregulated in culture. By reintroducing and restoring MYCT1 expression via a viral vector, they found that they were able to restore HSC self-renewal in culture and after transplant into host mouse models. These findings may enable the improved clinical use of HSC transplants in humans.

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) refers to the use of mature, differentiated cells as pluripotent stem cells capable of self-renewal and integration into a host body.2 This is accomplished by reprogramming harvested somatic cells using exogenous pluripotency factors, so that they take on the characteristics of stem cells, including the ability to self-renew and differentiate. The advantages are that they are autologous and therefore easily harvested and of low immunogenicity. Besides regenerative medicine, they are being investigated for modeling a patient’s specific disease in the lab, and testing drug efficacy and toxicity. Current research is investigating barriers to clinical use, such as low reprogramming efficiency, procedural complexity, and safety concerns due to tumorogenicity.2,3 Current studies are underway investigating the safety and viability of iPSCs for lab-grown dopaminergic neurons for treating Parkinson’s disease via intrastriatal grafting.4

External Cues

The non-embryonic stem cell host body niche includes factors that regulate stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. The delicate balance between stem cell dormancy and self-renewal, differentiation, and paracrine functions is largely a function of the dynamic niche environment, and the dysregulation of the tissue environment has been implicated in a number of disease processes, especially malignancies.5 Robust research is underway to understand the external factors that play a role in non-embryonic stem cell self-renewal and other functions in a host body and how the niche micro-environment can be manipulated to optimize the potential of stem cells for clinical applications.5 For example, cytokines from the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily have proven to be a rich source of ongoing research into controlling stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, with a number of clinically relevant host tissue applications.6

Reporter Lines

Work is underway to develop and exploit reporter systems that allow for monitoring and quantifying reporter genes without the need to destroy the stem cell sample under study.7 Reporter systems are used in stem cell self-renewal to engineer stem cells to express a reporter gene that is under the control of a desired promoter. This provides a modality for real-time monitoring of stem cell activity (including gene expression, promoter activity, and differentiation) using different assays, reducing sample heterogeneity. Among the applications in regenerative medicine is the isolation and removal of undesirable populations in transplant stem cell cultures.7

References:

1. Aguadé-Gorgorió J, Jami-Alahmadi Y, Calvanese V, et al. MYCT1 controls environmental sensing in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2024;630:412-420. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07478-x

2. Matiukhova M, Ryapolova A, Andriianov V, et al. A comprehensive analysis of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) production and applications. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1593207. doi:10.3389/fcell.2025.1593207

3. Moy AB, Kamath A, Ternes S, et al. The challenges to advancing induced pluripotent stem cell-dependent cell replacement therapy. Med Res Arch. 2023;11(11):4784. doi:10.18103/mra.v11i11.4784

4.Tabar, V., Sarva, H., Lozano, A.M. et al. Phase I trial of hES cell-derived dopaminergic neurons for Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2025;641:978-983. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08845-y

5. Turlo AJ. The microenvironment that supports stem cell maintenance. Persp - Stem Cell Res Regener Med. 2024;7(1):167-168. doi:10.37532/SRRM.2024.7(1)

6. Liu S, Ren J, Hu Y, Zhou F, Zhang L. TGFβ family signaling in human stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. cell regen. 2024;13(1):26. doi:10.1186/s13619-024-00207-9

7. Puspita L, Juwono VB, Shim J-W. Advances in human pluripotent stem cell reporter systems.

iScience. 2024;27(9):110856. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.110856.